Brazil Spotlight: "Brazil faces the worst drought and floods in nearly a century"

Water and energy shortages may threaten Brazil’s economic recovery from a recession caused by the Covid-19 pandemic

On May 29, the Brazilian Government declared a “water shortage alert” until September for the states of São Paulo, Paraná, Minas Gerais, Mato Grosso do Sul and Goiás. These states account for 70 per cent of the water storage capacity for hydroelectric power in the country.

A drought was recorded from February to April (typically rainy months) threatening the water supply—for consumption, electricity, agriculture, industry and river transport—and impacting the economy at a time when indicators point to a 5 per cent GDP growth in 2021.

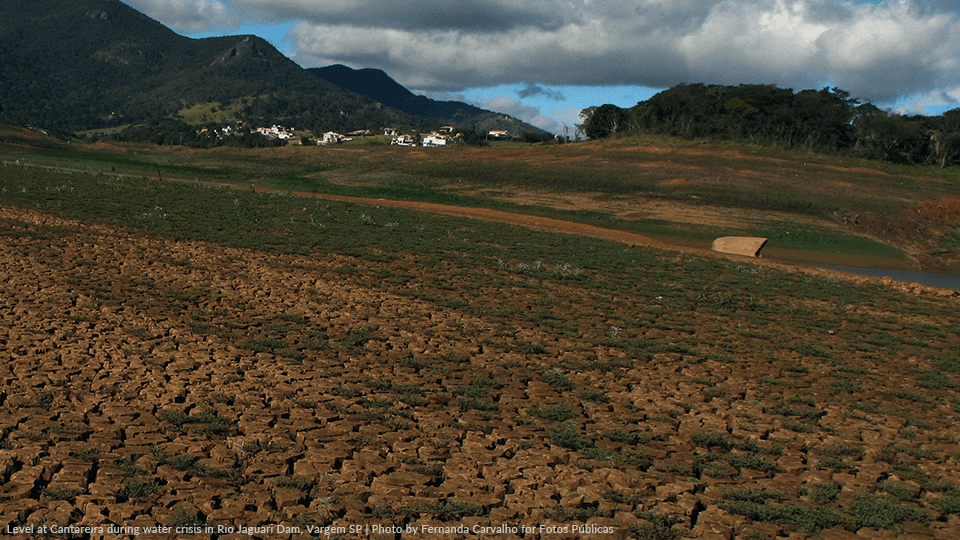

This is not the first time Brazil has suffered a water shortage. Despite having 12 per cent of the fresh water on the planet's surface, it is not evenly spread across the country: while the Southeast and Midwest are experiencing the worst recorded drought in 91 years, the North faces the worst flooding of the Rio Negro—a tributary of the Amazon—in 119 years.

"...drought caused 22 million inhabitants of the São Paulo greater metropolitan region to experience water shortages."

In 2001, a scarcity of rain combined with an increased demand for water, lack of infrastructure investment and deforestation at the source of rivers resulted in a series of power cuts that led to severe energy rationing across the country. At the time, 90 per cent of power generation was supplied by hydroelectric plants.

Consumers were forced to cut their electricity consumption by 20 per cent to avoid paying higher energy rates. As a result, household appliances were switched off, people raced to buy low-energy light bulbs and the search began for cheaper energy sources for manufacturing. The crisis triggered a recession that decreased GDP growth from 4.9 per cent in 2000 to 1.39 per cent in 2001.

In 2014, another drought caused 22 million inhabitants of the São Paulo greater metropolitan region to experience water shortages. The largest of the city's six reservoirs, the Cantareira Reservoir, spent 535 days using low-quality “dead volume” water—the water located below the intake pipes that draw from the reserve. In recent years, the state government has carried out several projects to increase the city’s water supply.

“According to the Brazilian Electricity Regulatory Agency, hydroelectric energy sources currently provide 59.5 per cent of Brazil’s total energy supply.”

After the 2001 power cuts, the National Integrated System (SIN) —a nationwide hydroelectric energy grid—underwent successive reforms, privatising assets to overcome the deficit in public investment, increasing the energy output capacity and enabling the expansion of alternative energy sources such as biomass, solar and wind. However, renewable sources are intermittent and unstable and have the added disadvantage that the energy cannot be stored and must be used as soon as it is generated.

The latest reform to SIN was triggered last May when Brazil’s lower house of congress approved the capitalization of Eletrobras, the sector’s largest public company whose state-controlled shares will be privatized. The Senate is due to discuss and approve the bill by the end of June.

After the 2001 crisis, power generation capacity was increased substantially. New hydroelectric plants—such as the Belo Monte, Jirau and Santo Antônio plants—were brought online, taking a high environmental toll. In order to avoid the risk of power cuts and energy rationing, multiple thermoelectric plants were built close to areas of high energy consumption.

While Brazil is better protected now from energy cuts, the thermoelectric plants have also had an environmental impact, increasing the burning of fossil fuels which generate greenhouse gases. Currently, there are 3,180 thermoelectric plants in operation, powered by gas, coal, diesel and biomass, responsible for 21 per cent of the electricity consumed in the country.

Despite this, conditions are favourable for Brazil to move towards a decarbonized economy, thanks to renewable energy generated by rivers. According to the Brazilian Electricity Regulatory Agency, hydroelectric energy sources currently provide 59.5 per cent of Brazil’s total energy supply; wind farms 9.8 per cent; biomass plants 8.3 per cent; natural gas plants 8.1 per cent; and other sources, such as solar, nuclear, coal and diesel 9.3 per cent. As such, with 83 per cent of electricity provided by renewable sources, the Brazilian power matrix is one of the cleanest and most sustainable in the world.

The fate of the looming 2021 crisis hinges on the drought, a result of the La Niña meteorological phenomenon in the Pacific Ocean (which reduces the surface water temperature, decreasing rainfall in the Mid-South region of Brazil) and the difficulty of structuring a power grid resistant to climate change in a deficit economy. Climate change makes it difficult to predict the flow and use of rivers.

In 2020, while rainfall was low, a crisis was averted because the Covid-19 pandemic reduced economic activity and energy consumption, decreasing Brazil’s GDP by 4.1 per cent. Ironically, the impact of the new drought hits at the same time as the country ramps up its production of materials for the Covid-19 vaccine rollout while the economy begins to recover from the recession.

Last week, the National Electricity System Operator (ONS) ordered a review of Brazil’s 3,180 thermoelectric power plants —belonging to 40 companies—to find out precisely their capacity in order to avoid the risk of power cuts and energy rationing.

"If the drought gets worse, the competition for water will increase…"

For now, no power shortages are being forecast, but the government will have to decide what to prioritize in the areas most affected by the drought. For example, dozens of hydroelectric power plants are located in the Paraná River basin and its tributaries, which is also home to most of the country’s agricultural and industrial production. Fifty-three per cent of the capacity of hydroelectric power generation in Brazil lies in the Paraná River basin, but it is currently only functioning at 27 per cent of full capacity.

To avoid rationing in the Southeast, the Brazilian Electricity Regulatory Agency will have to raise the price of energy at least 20 per cent and reduce reservoir flows, affecting other water usage. For example, river transportation on the Tietê-Paraná waterway is under threat. It is the most direct route to the port of Santos and is responsible for the transport of agricultural produce (in grain alone, 6 million tons per year) for export.

If the drought gets worse, the competition for water will increase, both for city consumption as well as energy production, industry, agriculture and transport.

This will be a fight between big dogs.

About Brazil Spotlight

Every month, Story Productions publishes a new Brazil Spotlight column by Ricardo Arnt, a Brazilian journalist and author with more than forty years experience. His works include director of Planeta magazine and TV Bandeirantes, editor of Exame magazine, Folha de São Paulo and Superinteressante (published by Editora Abril), and international editor of Jornal Nacional on TV Globo.

Subscribe to our newsletter and be one of the first to read the latest Brazil Spotlight column. From the economics of sustainability to deforestation in the Amazon, Ricardo will be tracking down the most interesting, topical stories one step ahead of the news cycle. We want to inspire TV producers and researchers around the world with inspirational ideas for their next production.

Learn more about the author behind our serial column. Send topic suggestions to press@storyproductions.com. Interested in covering something you've read here? Get a quote for your next production in Brazil.

Related stories

Brazil Spotlight archive

Share this story:

Get the latest news straight into your inbox!

Contact Us

Read another story